About the Project

By Fenwick McKelvey

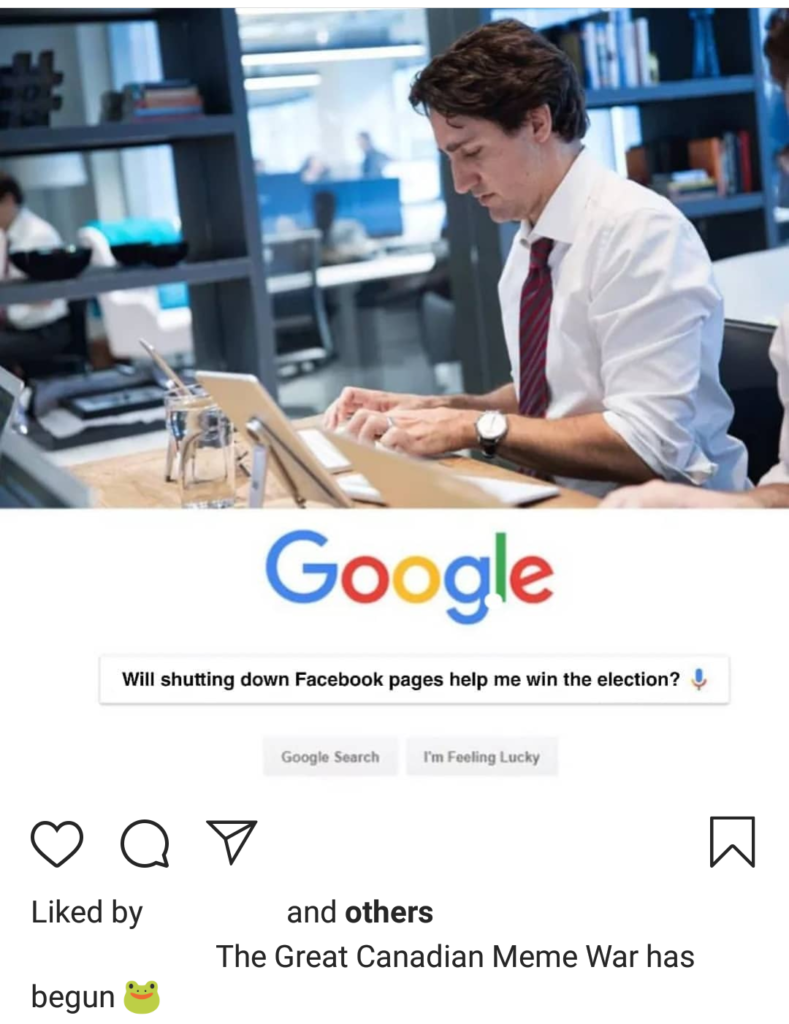

Our project was a first study of memes in elections in Canada. Experimenting with large-scale computational methods in cooperation with established methods of political communication, our research team tracked the publications of memes from 28 September 2019 to 28 October 2019. We mostly focused on memes posted to public Facebook groups, but we found Canadian political memes on Instagram, Reddit Twitter, and Tumblr.

Our project sought to:

- Help describe the most popular and most frequently shared memes during the Canadian federal election and analyze their political significance;

- Discuss how partisans differ in how they produce, modify and share memes in Canada; and,

- Map how memes circulate online.

Why Memes?

While Maclean’s magazine aspires to entertain its readers, it certainly didn’t expect its 7 November 2018 cover to be quite so entertaining. The cover labelled a photo of five Conservative leaders as “The Resistance” – a reference to anti-Trump movement south of the border. The comparison was too funny for Liberals and other partisans who could not rationalize comparing activism in the United States to the efforts of five politicians in Canada against the carbon tax. On social media, users mocked the cover by photoshopping it or recaptioning it as if to double-down on their perception that the cover was absurd. In effect, Maclean’s cover was made meme, becoming a moment of political frenzy, reminding citizens about politics and re-framing discussion of the carbon tax, for a moment.

Memes are referential images shared, modified and, in the case above, politicized online. The Maclean’s Resistance cover suggests that memes are a way of expressing and engaging in partisan politics, in this case allowing Liberals and anti-Conservative voters to constitute what Zizi Papacharissi calls “networked structures of feeling”.

Memes may be political, but we’re not sure how, at least in Canada. There was a rush after the election to overstate meme’s effect in Donald Trump’s election. But as Dr. Whitney Phillips, Dr. Gabriella Coleman and Dr. Jessica Beyer emphasize the popularity of memes about Trump and Trump himself “cannot and should not be tethered to online communities of the past. It was, instead, symptomatic of much deeper, much more immediate cultural malaise.”

Our project then looks to memes as a reflection of this deeper story of Canadian culture, looking to the popularity of memes to understand how partisans and publics relate to politicians and parties. There is little research about memes in Canadian politics (the notable exception being the work of Mireille Lalancette). We believe that through memes partisans and political spectators form and sustain feelings and attachments to parties and leaders.

When Canadians communicate, they share pictures. Some of these pictures are of friends, families, or maybe food. Other pictures are memes. Memes refer to “evolving tapestries of self-referential texts collectively created, circulated, and transformed by participants online” (Phillips & Milner, 2017, p.30). Memes help people express their emotions, share jokes, be fans, and, notable for our study, discuss politics. Canadians make memes about politics, but there are limited studies about how (Lalancette & Raynauld, 2019; Piebiak, 2014). Internationally, we know that memes are an important part of online mobilization and to build political affinities (Milner, 2016; Mina, 2019; Nissenbaum & Shifman, 2018), yet there have been no large-scale research project studying memes during a Canadian election.

Memes also defy current approaches to political communication and election studies. We are just beginning to understand how the short, visual, often humorous messages alter the popularity of political issues and the nature of partisanship.

References

Lalancette, M. and Raynauld, V. “The Power of Political Image: Justin Trudeau, Instagram, and Celebrity Politics”. American Behavioral Scientist Vol 63(7), 2019: 888-924.

Milner, R.M. 2016. The world made meme: public conversations and participatory media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mina, A. X. 2019. Memes to Movements: How the World’s Most Viral Media Is Changing Social Protest and Power. Boston: Beacon Press.

Nissenbaum, A. and Shifman, L. “Meme Templates as Expressive Repertoires in a Globalizing World: A Cross-Linguistic Study”. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication Vol 23(5), 2018: 294–310.

Phillips, W. and Milner, R. M. 2017. The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. Boston: Polity.

Piebiak, J. 2014. Appendices, Shit Harper Did: A community speaking truth to power? Masters thesis, Concordia University.