Political Memes Perform. It’s No Joke.

By John F. Gray (CEO) Mentionmapp Analytics Inc.

“Politics will eventually be replaced by imagery. The politician will be only too happy to abdicate in favor of his image, because the image will be much more powerful than he could ever be.” ― Marshall McLuhan

Memes are not simply an internet phenomenon, yet they would most likely not be such a recognizable cultural phenomenon without it. There is no one definition of a meme. Meme researcher Limor Shifman describes a meme as “(a) a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance, which (b) were created with awareness of each other, and (c) were circulated, imitated, and/or transformed via the Internet by many users” (2014, p. 41). Memes in our study meant graphics that had an ‘internet ugly’ aesthetic and used common references and fonts associated with internet culture rather than graphic design conventions (Douglas, 2014). The term “meme” is credited to Richard Dawkins from his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. He defined the “Meme, as unit of cultural information spread by imitation. The term meme (from the Greek mimema, meaning “imitated”). We might not have well established genre theory for memes, but it is time to recognize the significant difference between Grumpy Cat and today’s political memes.

Given the limited amount of research attention paid to memes overall and in particular to Canadian political memes, there is no shortage of questions to look for potential answers to. Being part of the Digital Ecosystem Research Challenge, The Great Canadian Encyclopedia of Political Memes project set about addressing the key questions:

- How do political issues or opinions about leaders circulate as memes?

- Can we distinguish political cultures by their distinct uses of memes?

As noted in DERC’s final report, Canadians made memes during the election and those memes matter for our political culture, but not for winning elections. Memes did not predict the outcome of the election. The final DERC final report did not include all of our research, so I would like to highlight some of our additional findings.

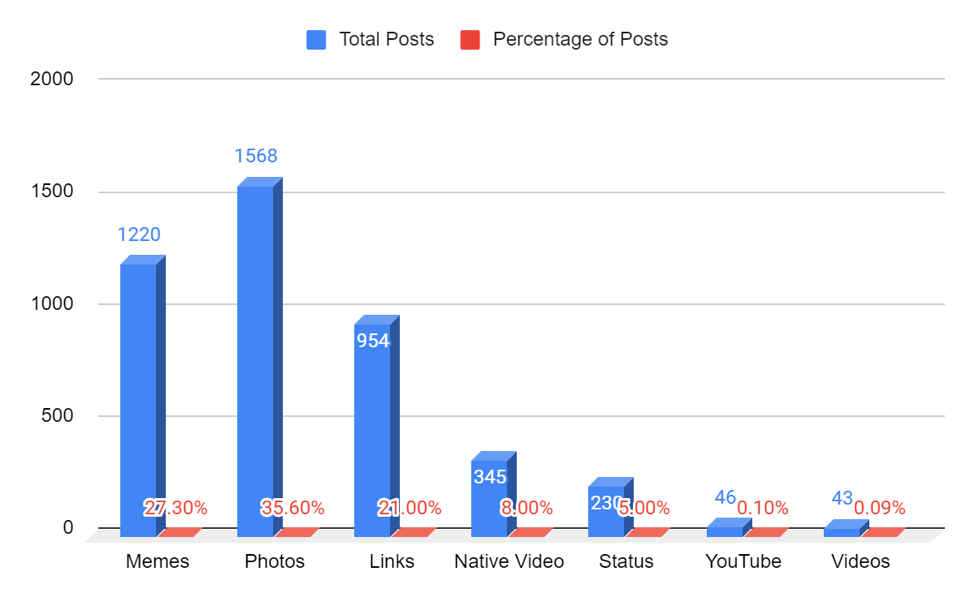

Being a member of the project team, I was given the opportunity to explore the question, how did memes perform compared to other content? Using Crowdtangle data, the subsequent analysis of the fifteen politically identified Facebook Pages engagement metrics, we first noted that memes represented 27.7% of the total content posted between September 28 and October 28, 2019. An anomaly (somewhat ironically): we noted that the Facebook page Canadian Political Memes had no identifiable memes for the research date range.

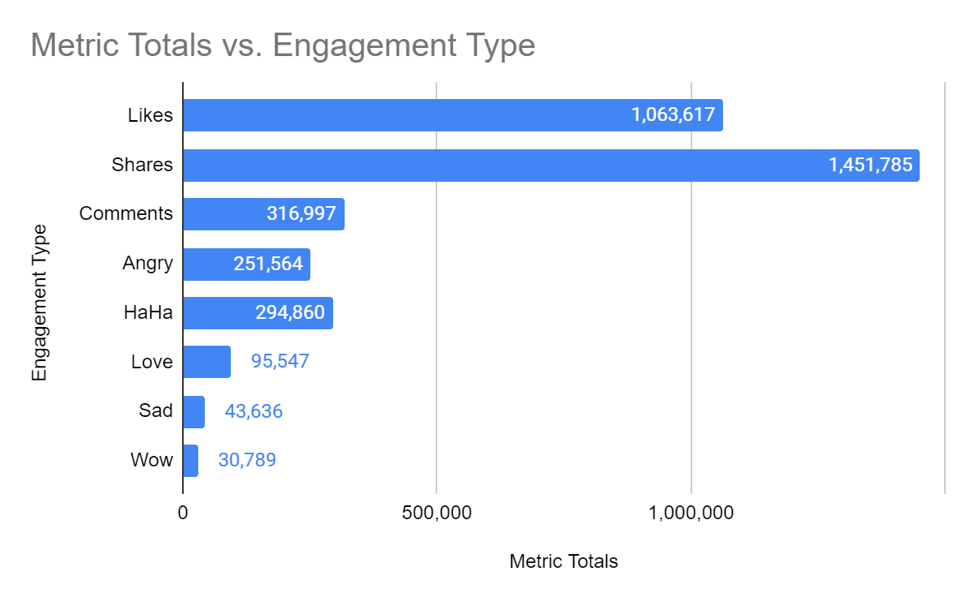

For our analysis of the provided Crowdtangle data, we considered these metrics for each page – Total Posts; Total URL (Memes); Total Links; Total Native Videos; Total Photos; Total Status; Total Videos; Total YouTube; Total Likes; Total Comments; Total Shares; Total Angry; Total Haha; Total Love; Total Sad; Total Wow.

Between September 28 and October 28, 2019 the fifteen Facebook Pages created 4406 Posts.

The Angry and HaHa emotive metrics perform better than Likes, Comments and Shares. In many ways these findings highlight how the social space operates on our emotions.

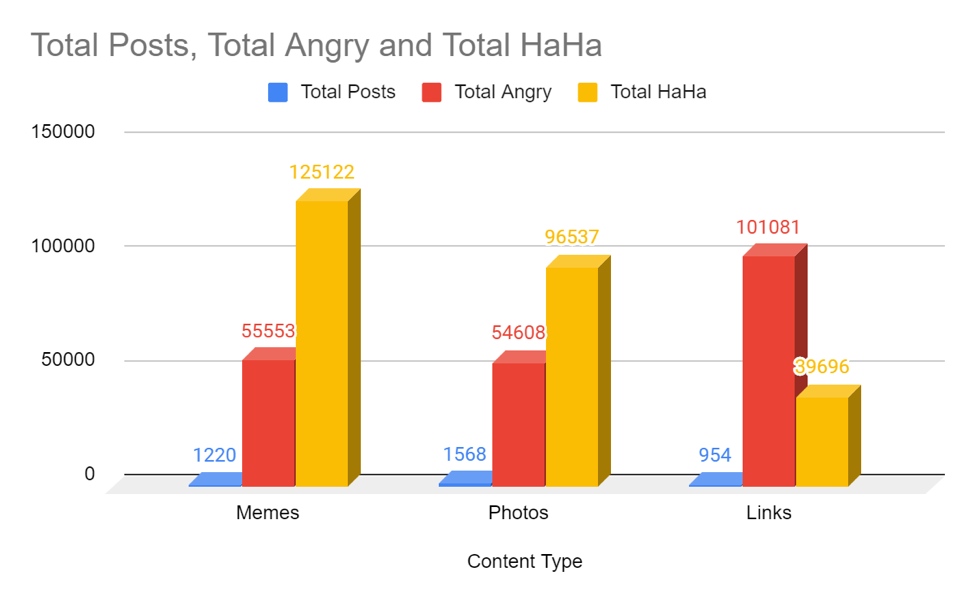

We can see that the total volume of Memes despite 348 fewer post generated a higher number of both Angry and HaHa emotive responses than Photos and further supports that these are high performing assets. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that Links generated the most Angry reactions (101081 total), which is just under double Photos & Memes Angry reactions together (110,161 combined). This dynamic could support the premise that outrage driven “clickbait” headlines are highlighly effective when it comes to driving engagement.

While our analysis shows that memes were the second most posted type of political content during the 2019 Canadian Federal election, more significantly, based on the overall post volume, and subsequent key engagement metrics it is clear that memes outperformed all other content.

In comparison, our DFRLab article Trudeaus and Trudeaun’ts — memes polarize in Canadian elections:Memes on Pinterest gamify polarization in Canadian elections further illustrates how memes perform in the information ecosystem. As a visiting research fellow working on this project, we focused on Justin Trudeau, and were able to analyze how Pinterest’s algorithm may contribute to the dissemination of extremist memes as recommended popular items on its app. Overall, “the results of the study showed that, by clicking on only a single hyperpartisan and often hostile meme, the platform would recommend other politically intense memes.”

It is evident that the creation, distribution, and sharing of Mimetic political content played an important role in the overall communication strategy. This research further suggests we need to take Memes more seriously. We need to recognize a range of key considerations such as:

- Low cost (unlike creating or buying bots or “deep fakes”)

- Easy to create (countless free tools for creation; internet itself is a vast library of images to access; socially cavalier attitudes towards copyright; bad guys with bad intent don’t care about rules)

- Easy to distribute across entire online ecosystem, from platforms (open… Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Reddit, Tumblr, Medium; 4Chan); closed platforms (WhatsApp, Snapchat); easy to anonymous websites publishing platforms such as WordPress, and Blogger.

- Easy to share,

- Easy the “get” almost regardless of literacy levels,

- Easy to defy attribution,

- Can serve to frame “strategic political narratives”,

- Blur the lines between satire, political propaganda and disinformation.

We can conclude that Prime Minister Trudeau’s unpopularity (memetically speaking) did not signal his electoral loss. For instance, the Conservative leaning Canada Proud Facebook efforts, where memes made up 20% of its top posts, did not lead to massive growth of membership larger than its Ontario base. It grew by only 13,000 followers over the course of the campaign to 162,346 as opposed to the roughly 400,000 followers of Ontario Proud. By contrast, progressive North 99 hardly used memes at all in its communication strategy. These findings suggest the effects of meme-jacking need to be better qualified with research on offline campaign activities.

Joan Donovan notes in her article, How memes got weaponized: A short history, that “great memes are authorless. They move about the culture without attribution.” These two qualities (harms be damned) ensure political memes will be an explosive ordinance proliferating across the information landscape. We can’t deny Grumpy Cat is funny. And, we can’t deny that political memes are serious business. They’re no joke.